Pope: Holy See's 'positive neutrality' in conflicts is not ethical neutrality

On the day Ukrainian President Zelensky is expected at the Vatican to the new ambassadors received for their letters of credentials Francis returned to talk about the "piecemeal third world war" and the commitment of papal diplomacy to the defense of the dignity of every person and the promotion of fraternity among peoples. A thought "to the beloved Syrian people" tried by the earthquake and the long conflict.

Vatican City (AsiaNews) - The Holy See is working to contribute to conflict resolution through the exercise of "positive neutrality," which does not, however, mean "ethical neutrality," "especially in the face of human suffering."

On the day of his long-awaited meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky - expected at the Vatican this afternoon - Pope Francis returned as early as this morning to reiterate the urgency of the commitment to peace in the context of what he once again returned to calling the "third world war in pieces."

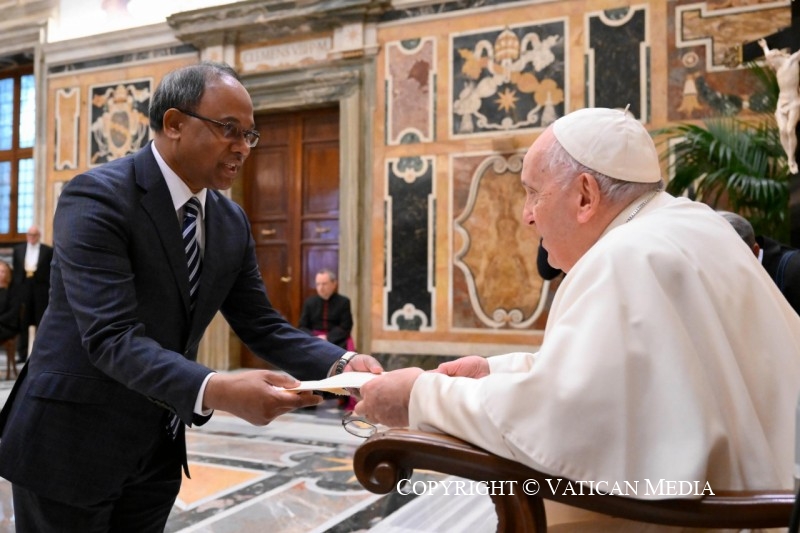

The Pope was speaking at an audience with the new ambassadors of Iceland, Bangladesh, Syria, Gambia and Kazakhstan on the occasion of the presentation of their letters of credentials.

"If we look carefully at the current situation in the world," the pontiff said as he met them in the Clementine Hall, "even a superficial glance could leave us disturbed and discouraged. We think of many places such as Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Myanmar, Lebanon and Jerusalem, which are facing clashes and unrest. Haiti continues to experience a serious social, economic and humanitarian crisis. Then, of course, there is the ongoing war in Ukraine, which has brought untold suffering and death. In addition, we see the flow of forced migration increasing, the effects of climate change, and a large number of our brothers and sisters around the world still living in poverty due to lack of access to clean water, food, basic health care, education, and decent work. There is, without a doubt, a growing imbalance in the global economic system."

"When will we learn from history," he asked, "that the ways of violence, oppression and unbridled ambition to conquer land do not serve the common good? When will we learn that investing in people's well-being is always better than spending resources on building lethal weapons? When will we learn that social, economic and security issues are all interrelated? When will we learn that we are one human family, which can only truly thrive when all its members are respected, cared for and able to contribute in original ways?"

To the ambassadors, the pope indicated the importance of the task they are called to perform in this regard. "Even the apostle Paul used this term to describe heralds of Jesus Christ (cf. 2 Cor. 5:20)," he recalled.

"As a man or woman of dialogue," he added, bridge-builder, the ambassador can be a figure of hope. Hope in the ultimate goodness of humanity. Hope that common ground is possible because we are all part of the human family. Hope that the last word is never said to avoid conflict or resolve it peacefully. Hope that peace is not a pipe dream."

In the current context, Francis acknowledged, this is not an easy task: "The voice of reason and calls for peace often fall on deaf ears," he commented. But precisely to keep hope alive also aims the diplomatic action of the Holy See, which "in conformity with its own nature and its particular mission, is committed to protecting the inviolable dignity of every person, promoting the common good and fostering human fraternity among all peoples."

Greeting, finally one by one, the new ambassadors, the pope addressed a special thought "to the beloved Syrian people, who are still recovering from the recent violent earthquake, amidst the continuing suffering caused by the armed conflict."

.png)