Pakistan faces a food crisis like a country at war

FAO and the World Food Programme sound the alarm. The long-term effects of last summer's floods, from which the country has yet to recover, are compounded by political and financial instability. With imports cut because of the lack of foreign currency, food is increasingly out of reach for many while inflation is way up.

Islamabad (AsiaNews) - Pakistan suffers from food insecurity like a country at war due to political instability, economic shocks, and last year's devastating floods from which the country has yet to recover.

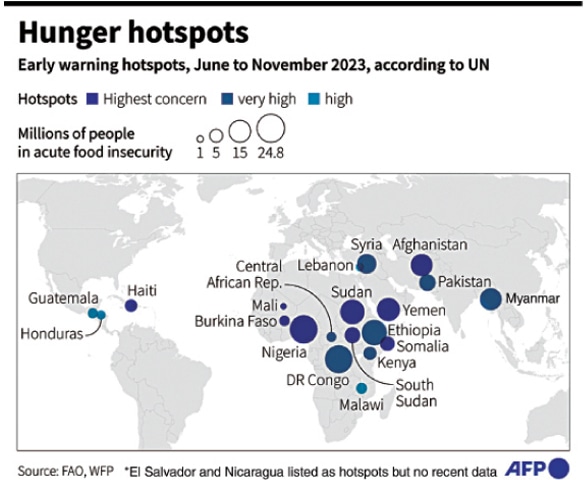

In their latest report, released yesterday, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) note that acute food insecurity is set to rise in the coming months in 22 countries around the world, most of them affected by conflict.

The highest concern level touches Burkina Faso, Haiti, Mali, Sudan and South Sudan, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Somalia, and Yemen. But not far behind are the Central African Republic, Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Pakistan, Syria as well as Myanmar, which has been torn apart by civil war since the military seized power in a coup on 1 February 2021.

People in all these countries are affected by acute food insecurity and their conditions could get worse due to political, economic, and environmental factors.

Food security is measured according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification index, which includes five phases: from general food security and moderate insecurity to the acute phase, emergency, and finally famine.

According to the UN data collected from three of Pakistan’s four provinces between September and December 2022, some 6 million Pakistanis suffer from acute food insecurity and 2.6 million face an emergency in a country of over 230 million.

The UN believes that conditions are likely to worsen by the end of the year due to the country’s ongoing political-financial crisis that is cutting into the purchasing power of many families and reducing their capacity to buy food.

Between April 2023 and June 2026, Pakistan is facing the prospect of repaying US$ 77.5 billion of external debt, a huge amount considering that its GDP was US$ 350 billion in 2021.

Political instability has so far stopped the International Monetary Fund and partner countries from extending new loans.

At present, the country is in the grip of open confrontation between a military-backed government and former Prime Minister Imran Khan, whose arrest earlier this month sparked violent protests across the country.

Unrest is expected to increase ahead of elections next October, while insecurity due to the terrorist threat is already rising in some regions.

Meanwhile, 15.3 million people are expected to face acute food insecurity between May and October 2023 in neighbouring Afghanistan, with some 2.8 million people in an emergency situation, as a result of the loss of foreign financial support, which has plunged the country into a deep economic crisis after the Taliban took power again in August 2021.

In Pakistan, depleted foreign reserves and the depreciation of the country’s currency are reducing the ability to import food, spiking inflation, and forcing the government to impose energy cuts owing to a lack of fuel.

Food inflation went from 8.3 per cent in October 2021 to 15.3 per cent in March 2022, then to 31.7 per cent in September 2022, and finally 35 per cent in December 2022. For day labourers, who earn on average two dollars a day, this has meant a 30 per cent loss in purchasing power.

The current situation is largely the consequence of last summer’s floods, which covered two thirds of the country. More than 11 million livestock were killed and more than 9.4 million acres of cropland (about 80 per cent of all the farmland in the country) were wiped out in Balochistan and Sindh, provinces already affected by food insecurity.

According to the World Bank, food production in some parts of South Asia was disrupted by higher-than-normal monsoon rains and less-than-normal rainfall in others.

.png)