Debt of poor countries, a matter of justice

Twenty-five years after the 2000 campaign, Pope Francis marks the Jubilee relauncing an appeal in the footsteps of from John Paul II to forgive loans to those who cannot repay them. The denunciation of a UNCTAD report: ‘Worldwide 3.3 billion people live in countries forced to pay more money for interest on debt than for education and health. The South of the world has paid the heaviest bill for the crises’.

Milan (AsiaNews) - "Another heartfelt appeal that I would make in light of the coming Jubilee is directed to the more affluent nations. I ask that they acknowledge the gravity of so many of their past decisions and determine to forgive the debts of countries that will never be able to repay them. More than a question of generosity, this is a matter of justice."

In the appeal to hope that Pope Francis is launching to the world with the Holy Year of 2025 that has just begun, these words from the Bull of Indiction Spe non confundit forcefully return to the theme of the public debt of the poorest countries. It is also taken up in this year's message of the pontiff for the World Day of Peace, entitled ‘Forgive us our trespasses: grant us your peace’.

This is not a new theme for a Jubilee: back in the year 2000, John Paul II had already asked for this idea from biblical roots to be made his own at the transition from one millennium to the next.

So 25 years ago, debt forgiveness also became an important theme for civil society. In our country it took the form of a campaign (supported by the Italian Episcopal Conference) that led to the cancellation of the bilateral debt that two African countries, Zambia and Guinea Conakry, had contracted with Italy and were no longer able to repay.

Other gestures - also financially very significant - took place at the same time in different countries.

Why does Francis now feel the need to relaunch this theme? Because - especially in recent years, as a result of the global crisis triggered by the pandemic and aggravated by the repercussions of the conflict in Ukraine - in so many countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia the issue of public debt has re-exploded in a very harsh way.

‘We are faced with a crisis that generates misery and anguish, depriving millions of people of the possibility of a dignified future,’ says Pope Francis, giving them a voice. ’No government can morally demand that its people suffer deprivation that is incompatible with human dignity.

Someone might ask: but if they are poor countries, why do they go into debt? Every economy relies on credit to finance its investments. It is no coincidence that the country with the highest share of public debt is the United States, i.e. the world's leading economy, followed (but at a great distance) by China.

Just to give an idea of the proportions: according to some data processed by UNCTAD - the UN agency for trade and development - at the end of 2023 the public debt reached the (record) figure of about 97 trillion dollars globally. Of this, however, over 33 trillion dollars is US debt. Italy's entire public debt exceeds trillion. All of the African countries taken together comes in at just over 2 trillion dollars.

But if it is relatively small in absolute terms, then why does debt in the poorest countries create so many problems? Because the conditions for contracting it are not the same for everyone.

Just as it happens to those who apply for a loan at a bank, countries are not treated equally by other states, multilateral bodies (such as the International Monetary Fund, IMF) or private individuals, the three big lenders.

The more fragile an economy is, the higher the interest rates to be repaid. For an African state, the same amount of money borrowed today costs 10 or 12 times more than in Germany or the United States.

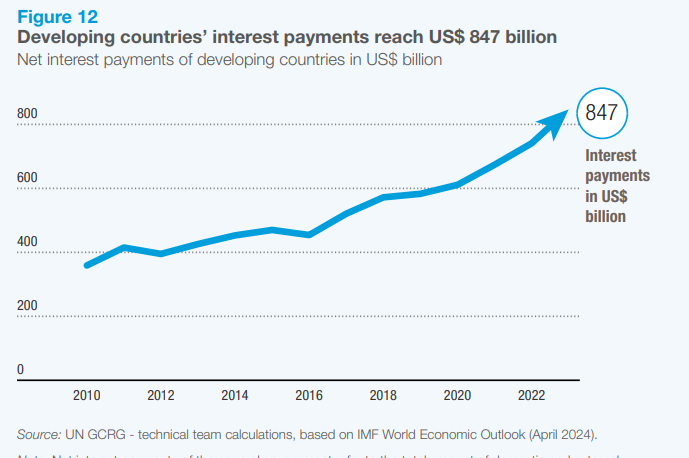

It is precisely this gap that has become increasingly untenable in recent years: African countries are currently paying 163 billion dollars a year for interest on their debt, compared to 61 billion they were paying in 2010.

This is a ballast on development possibilities. This is well explained by UNCTAD in an interesting report entitled ‘A World of Debt’, published a few months ago. Analysing the events of the last few years, it becomes clear that the bill for the repeated crises that we have all experienced since the pandemic has been paid far more heavily by poor countries.

‘The debt crisis is a hidden crisis,’ explains Giovanni Valensisi, an Italian economist at UNCTAD who is one of the editors of the report. ’In the overall picture, the figures involving developing countries would seem small. But if you look at what they cause in their societies, the impact is enormous'.

More than 3.3 billion people in Africa, Latin America and Asia, for example, now live in countries that are forced to spend more money to repay the interest on debts they have incurred than to finance health or education. In half of the developing countries, more than 6.3 per cent of all revenue generated by exports goes to repay creditors.

This is an unfair ‘tax’ on poor countries: UNCTAD recalls that when the London Agreement on Germany's war debt was signed in 1953, it was stipulated that the interest paid by the Germans should not exceed 5% of the revenue generated by exports, so as not to undermine their recovery.

Today, however, for dozens of countries in the South, this elementary principle of a future-oriented economy is not enforced.

But during the pandemic, wasn't debt aid envisaged for poor countries? ‘In 2020,’ answers Valensisi, ’the G20 countries had frozen interest payments on their debt to developing nations for two years.

That pause, however, ended just when the war in Ukraine had made the situation even worse, because the monetary policies adopted by the economically stronger countries themselves to contain inflation had caused all interest rates to skyrocket’.

No new interventions came at that point. And in a context in which 61% of the debt of developing countries, by now, is no longer lent by states or multilateral creditors, but by private individuals (banks or investors who buy particular financial instruments), there has even been an opposite effect: ‘The problem is the volatility of these sources of financing,’ comments the UNCTAD economist.

As soon as the yields of public bonds in the most developed countries rose, the choices of savers changed, abandoning the other markets. So in 2022 - just when they would have needed the resources most - the most economically fragile countries found themselves having to pay more money in interest to banks and private investors than they were receiving in new loans'.

There is the observation of these perverse mechanisms, therefore, behind Pope Francis' call to bring the issue of debt back into the spotlight on the occasion of this Jubilee. With the awareness, however, that today forgiving large portions of it is a more complex operation than 25 years ago.

Because the wider involvement of private investors multiplies the interlocutors with whom this act of justice must be negotiated. This is why the Pontiff also urged to take an extra step: to imagine ‘a new international financial architecture that is bold and creative’. In order to ensure that the burden of tomorrow's crises does not once again end up on the shoulders of the poor.

There are some ideas on the table: ‘A first step,’ Valensisi explains, ‘would be to address the issue of representativeness: to really involve developing countries in a meaningful way at the tables where decisions are taken. But we are also thinking about mechanisms to tackle the problem of excessive debt costs: one hypothesis is to strengthen the multilateral and regional development banks, both in terms of capitalisation and consequent lending capacity, and by having them amortise part of the risks, issuing a share of the loans in local currencies. Above all, however, there is a need to increase financial sensitivity in granting loans that give priority to projects in poor countries that create long-term development'.

These are just examples of a possible path. So that - as in the biblical idea of the Jubilee - we can all really start over again together.

12/02/2016 15:14

07/02/2019 17:28

11/08/2017 20:05

.png)