WHO: two thirds of new hepatitis cases reported in Asia (and two African countries)

According to the UN health agency, about 3,500 people die of viral hepatitis every day. The highest number is in China, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Pakistan. Despite improvements in diagnostic testing, huge disparities still exist in access to drugs.

Milan (AsiaNews) – About 3,500 people die every day from viral hepatitis, this according to a recent report released by the World Health Organisation.

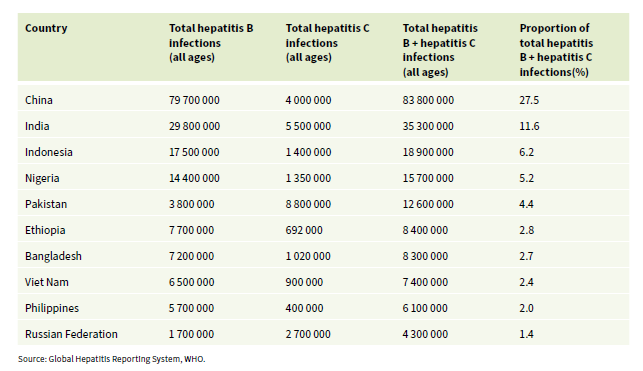

Although improvements have been made in diagnostics and treatments, a dozen countries, most of them in Asia, account for two thirds of hepatitis B and C cases, namely Bangladesh, China, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Russia, and Vietnam.

In the Western Pacific region, which accounts for 47 per cent of hepatitis B deaths, treatment coverage is 23 per cent, far too low to reduce mortality, the UN agency said.

“This report paints a troubling picture: despite progress globally in preventing hepatitis infections, deaths are rising because far too few people with hepatitis are being diagnosed and treated,” said WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver and can be viral. Among them, five viral forms exist, identified by letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E. B and C especially can take on a chronic form and lead to other diseases, like liver cirrhosis and liver cancer.

The WHO estimated an increase in deaths from 1.1 million in 2019 to 1.3 million in 2022, 83 per cent caused by hepatitis B and 17 per cent by hepatitis C.

Pakistan recorded the highest number of hepatitis C viral infections in the world, with an estimated 8.8 million cases, or 44 per cent of all new hepatitis C infections reported worldwide, attributed mostly to unsafe medical injections.

If hepatitis B is counted, we get a total of 12.6 million cases in 2022, or 4.4 per cent of total cases, placing the South Asian country in fifth place in world ranking behind China, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria, some of the most populous countries in the world.

The worst situation is in China (pictured). In 2022 it reported 83.8 million new infections (two types of hepatitis), or to 27.5 per cent of all cases worldwide.

India, which is in second place, has far fewer cases, 35.3 million or 11.6 per cent, while Indonesia comes in third at 18.9 million (6.2 per cent), followed by Pakistan (see above), Bangladesh with 8.3 million, Vietnam, 7.4 million, the Philippines, 6.1 million, and Russia with 4.3 million, the last three with less than 2.5 per cent of reported cases.

Since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, which slowed down health systems around the world, “There is a window of opportunity in 2024–2026 to get the global hepatitis B and C response back on track towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals,” reads the WHO report.

Reducing the number of cases of hepatitis over the next two years “requires treating an estimated 40 million people with hepatitis B and curing an estimated 30 million people with hepatitis C by the end of 2026.”

Yet, despite marked improvements in the diagnostics of the disease, the cost of treatment in some countries continues to be prohibitive, with great disparities from one country to another.

Pakistan, for example, had the lowest price for a 12-week course of treatment with daclatasvir and sofosbuvir, two drugs used for hepatitis C, which costs about US$ 33. In China, the price rises to US$ 10,000, the highest in the world.

While hepatitis B drugs in China and India cost about US$ 1.20, well below the world average, in Russia, they cost more than US$ 34.

Meanwhile, the latest drug, Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF), which replaces tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), has not been approved in all countries of the world, causing huge disparities.

05/05/2022 13:24

25/03/2006

.png)