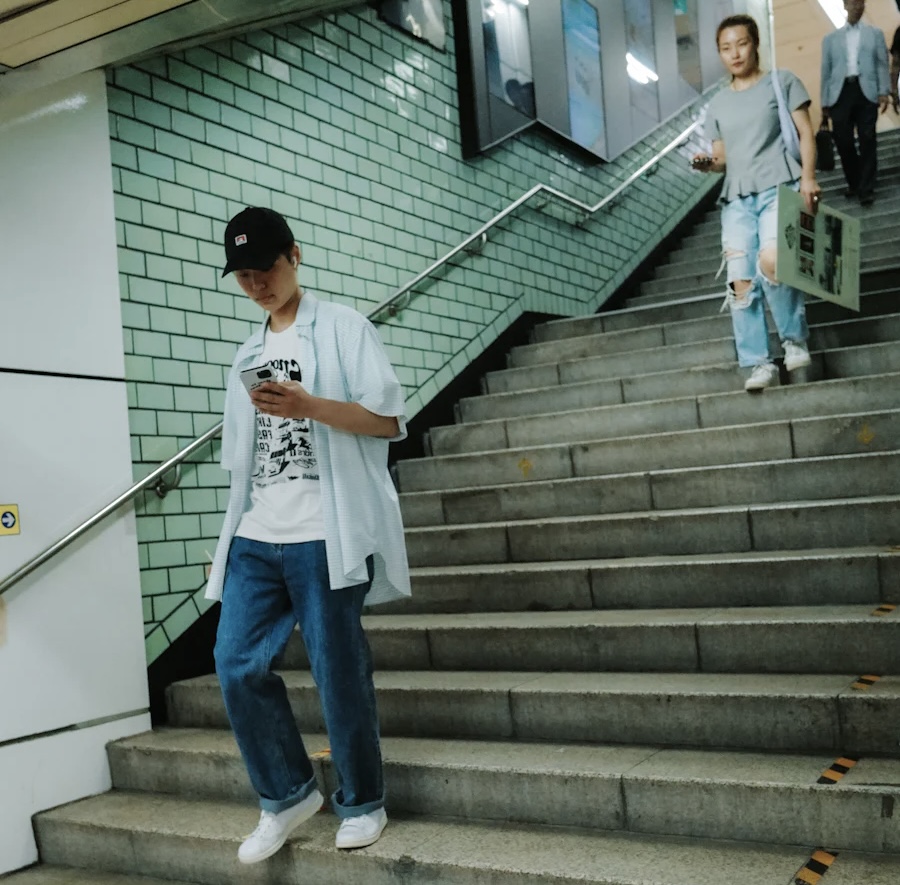

Seoul, the ‘cold demographic winter’ of young people: without family, home and children

In an essay published in La Civiltà Cattolica, Jesuit Jeong Yeon Hwang looks inside the crisis experienced by young people today, reflected by the collapse in the birth rate. Extreme competition right from school causes ‘burnout and isolation’. But for 94.8% the imagined future is ‘attainable’ and 95.7% give a ‘priority’ role to relationships.

Milan (AsiaNews) - South Korea is experiencing ‘the coldest demographic winter’, borrowing the term coined by Pope Francis to describe a low birth rate, with a provisional figure for 2022 of 0.78 falling to 0.72 for 2023, and then plummeting to 0.68 according to estimates for 2024.

But what are the reasons behind this phenomenon? And what does the demographic crisis say about young Koreans today? This is the issue addressed in the latest issue of the magazine La Civiltà Cattolica by Jesuit Fr Jeong Yeon Hwang, who tries to look inside the so-called ‘Opo generation’ (the ‘five no's’ generation in Korean), that of those who today seem to be giving up dating, getting married, having children, owning a house and having a career.

Seoul has proposed economic incentives, cash rewards, childcare subsidies and reimbursements for infertility treatment. Nevertheless, the declining birth rate is a trend that has intensified approaching an all-time low ‘unprecedented in the modern era worldwide’. Among the triggering factors are job insecurity, poor housing affordability, the high cost of living reflected in childbearing, and a family-unfriendly culture in the workplace.

But financial difficulties are compounded by the growing competitiveness in education first, then in the workplace and social spheres referred to as ‘credentialism’: it is based on university degrees and government-accredited certifications for high-income professions, such as doctors and lawyers.

These titles are synonymous with high status and end up fuelling competition from an early age, extending through the different stages of growth into adolescence and adulthood. Proof of this is the fact that before university about 80% of students attend ‘hagwon’, private institutions for tutoring those preparing to enter high schools or the most prestigious universities. In Seoul alone, there are over 24,000 of them, a number far greater than that of convenience stores.

On the one hand, South Korea is among the countries with the highest rate of education in the world, with around 88% of women and 83% of men aged between 19 and 34 having a degree or attending a university; however, the country faces unemployment and difficulties in buying a house, factors that force young adults to delay marriage plans and, very often, to give up on planning a family.

The data reflect the crisis: the age at which women - who are increasingly struggling to reconcile marriage, bringing up children and a working career - marry has risen from 26.5 years in 2000 to 31.2 in 2022, while the percentage of ‘lifelong’ singles has risen from 5% in 2013 to 14% in 2023.

The analysis also shows an increase in ‘gender polarisation’ among 20-35 year olds, impacting the 2022 elections: 75.1 per cent of men aged 18-29 supported a conservative candidate, while 67 per cent of women in the same age group expressed a preference for a progressive.

This translates into a ‘resistance’ among men to policies aimed at improving women's rights, so much so that the gender pay gap in 2022 was 31.2%, the highest among OECD countries. On average, women earn far less than their male colleagues and women's representation in politics is only 19%, among the lowest OECD.

There are also significant differences when it comes to marriage and children. Among unmarried young adults, 75.3% expect to do so in the future, a difference of 10.1 points between men and women (79.8% men, 69.7% women). 63.3% also expect to have children in the future, and here the difference between men and women stands at 15.2 points (70.5% men, 55.3% women). Young women and young men - the article notes - live in competition and have diametrically opposed political views and different attitudes on marriage and family.

Young adults are under constant pressure from an early age in the race for success, risking ‘burnout and isolation’. According to a 2022 survey, 33.9 per cent of young adults have experienced it in the past year due to career-related insecurity (37.6 per cent), work overload (21.1 per cent), scepticism about work (14.0 per cent) and work-life imbalance (12.4 per cent).

In addition to the risk of burnout, South Korea has one of the lowest scores for social relationships: 21.5 per cent of this group state that they have ‘no friends or family to turn to in case of need’, well above the average of 10.1 per cent, and the risk of social isolation is also high.

Even in such a competitive society, however, young people do not lose their vitality: 94.8% are convinced that their imagined future is in some way ‘attainable’ and 95.7% recognise a ‘priority’ role for relationships with positive people in their lives.

This is why young people still cultivate dreams of happiness and love, and there is a growing desire for solidarity, a union, observes Fr. Jeong Yeon Hwang, that ‘can guarantee a shared vision and give the necessary strength to realise it’.

.png)