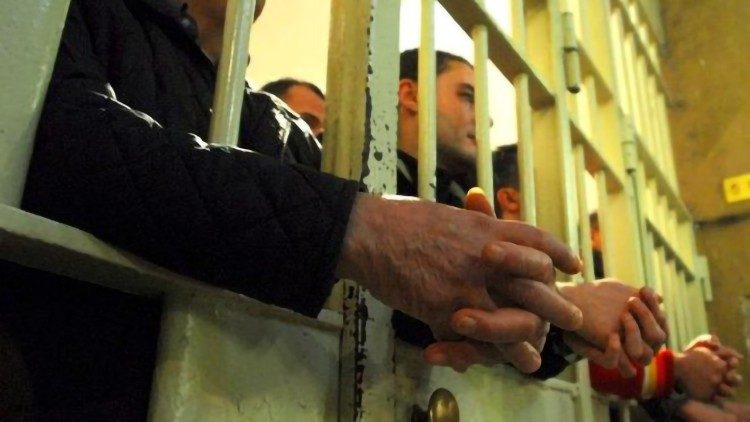

More and more deaths in Sri Lankan prisons

Suicides are up, especially by hanging. Some 631 inmates died in the last four years, from, among others, assaults, riots, disease, psychological disorders, and drug abuse. The Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka calls for greater protection, like taking inmates’ picture immediately after arrest.

Colombo (AsiaNews) – Sri Lankan prisons have seen a disturbing rise in deaths among inmates, nearly 50 from suicide, as well as poor health, and violence.

Last year, 209 deaths were reported, said Gamini B. Dissanayake, Commissioner of Prisons. The number this year is higher; especially alarming is suicide, which the system is failing to prevent. Seventeen cases were reported in 2023, including three foreign nationals.

Following a request under the Right to Information Act, the Department of Prisons released data showing that 631 inmates, both suspects and convicts, died in prison in the past four years, 61 by hanging, 18 in 2020, 14 in 2021 and 2022, and 15 in 2023.

Most inmates who die in prison from disease are men, but 18 were women. About 357 inmates who died in prison had not been convicted.

Many inmates died in violent incidents, sparked by overcrowding and poor facilities; in 2020, for instance, 11 prisoners died in a riot that broke out at Mahara Maximum Security Prison, while two were shot dead during a riot in Anuradhapura Prison.

One prisoner lost his life, electrocuted, on a rainy day when a power line fell on him. In Negombo Prison, a detainee was beaten to death by his cellmates.

Last year, three prisoners drowned in the Mahaweli River, trying to escaping from Pallekele Prison in Kandy. Another was killed trying to break out of Kegalle Prison. Another fell from a coconut tree he had climbed after escaping from Pallansena Prison in Negombo.

Kasun Withanage and Anusha Samanthilaka, human rights lawyers, spoke to AsiaNews about the issue.

A study by the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) notes that there are several factors behind the deaths; they include “Violence inflicted by prisoners and prison officers that ultimately caused death.”

Those who died “were in a state of distress, most often suffering from drug withdrawal symptoms or effects of a psychological disorder.” The latter affect the health of inmates, and are often used to justify the use of violence to subdue them.

For the lawyers, the HRCSL study indicates that “it is necessary to identify marks and photograph an inmate upon entry as it could place a timestamp on any injuries acquired by prisoners prior to imprisonment.” This would help “in determining, whether an assault was committed on a prisoner inside the prison or prior to entry.”

The goal is to achieve greater transparency and ensure that abuses against incarcerated people are traceable, avoiding worsening their state of fragility.

Under current rules, anyone brought in the evening can only be examined the next day due to the lack of staff. Thus, “if a new prisoner is assaulted during his/her first night prior to registration, it may not be possible to ascertain whether the injuries were inflicted in prison or during arrest.”

For psychologist Ruwan Dissanayaka, “when prisoners are placed in solitary confinement, the majority engage in self-harm, displaying suicidal tendencies.”

What is more, “The aggravation of the symptoms displayed by persons suffering mental illnesses along with lack of medical treatment foster suicidal tendencies and most inmates succumb to them.”

Because of the lack of staff to provide overnight surveillance, violence among inmates can break out in most Sri Lankan prisons, since officers on duty are unable to perform their patrol work.

Sometimes, those wounded in fights do not have access to medical care, especially overnight emergency care, and this has contributed to some deaths in prisons.

.png)