Israeli scholars use artificial intelligence to translate Akkadian

Experts from Tel Aviv University and Ariel University have created a program to translate an ancient language that is difficult to decipher, allowing automatic and accurate translation from cuneiform characters into English. It is an example of human-machine collaboration in an area with few human experts. Hundreds of thousands of tablets are still inaccessible.

Tel Aviv (AsiaNews) – A group of Israeli researchers from Tel Aviv University and Ariel University have developed an artificial intelligence model to translate into modern English texts in Akkadian, an ancient language written in cuneiform, an often painstaking task hitherto performed by historians, linguists and translators.

Experts in Assyriology, who specialise in the archaeological, historical, cultural and linguistic study of ancient Mesopotamia, have spent years trying to decipher texts in cuneiform, one of the oldest-known forms of writing.

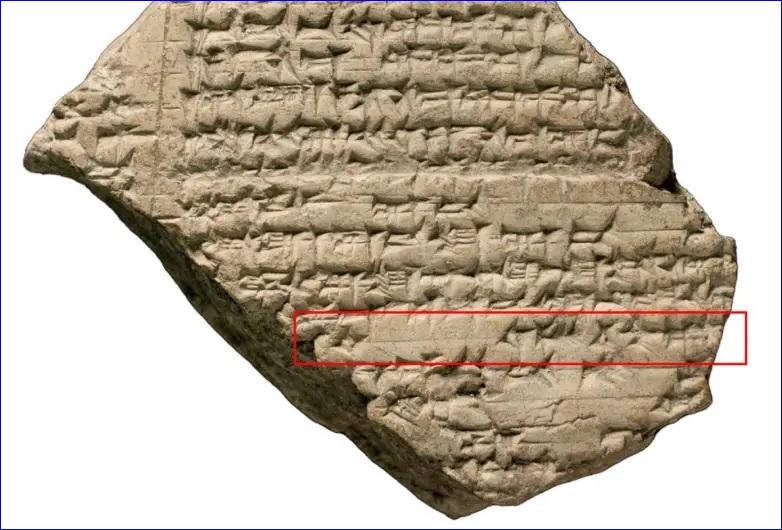

Cuneiform means wedge-shaped because the language was written by making a wedge-shaped mark on a clay tablet.

Spoken in ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), Akkadian was an Eastern Semitic language used in particular by the Assyrians and Babylonians. It is the oldest known Semitic language, based on a writing system first used by the Sumerians.

The language takes its name from Akkad, the capital of the Akkadian Empire founded by King Sargon. The city was the largest of its time although no traces have been left.

Over the decades, archaeologists have found hundreds of thousands of clay tablets written in cuneiform, dating as far back as 3,400 BC, far more than scholars who can understand and translate them can handle.

Shai Gordin of Ariel University, Jonathan Berant and Omer Levy of TAU, along with others recently shared the fruits of their studies in the peer-reviewed journal PNAS Nexus in an article titled "Translating Akkadian to English with neuronal machine translation”.

During the design phase, two versions of the machine-learning versions model were developed, one that translated Akkadian from cuneiform signs into Latin alphabet and another from Unicode representations of cuneiform signs.

The first, using Latin transliteration, gave the best results, scoring 37.47 in the Best Bilingual Evaluation Understudy 4 (BLEU4), which assesses the correspondence between human and machine translation of the same text.

The program proved particularly effective translating short sentences of 118 or fewer characters. But it also produced “hallucinations" (syntactically correct but inaccurate text).

The program could prove particularly useful in the first phase of translation, in “human-machine collaboration” leaving humans the task of correcting and refining the model’s output.

Cuneiform manuscripts covering the political, social, economic, and scientific life of ancient Mesopotamia number in their hundreds of thousands; yet, “most of these documents remain untranslated and inaccessible due to their sheer number and the limited quantity of experts able to read them."

Translation, the paper says, is “a complex process, since it commonly requires not only expert knowledge of two different languages but also different cultural milieus.”

With this in mind, "Digital tools can assist” through “optical character recognition (OCR) and machine translation.”

All said, ancient languages remain a great challenge. “Their reading and comprehension require knowledge of a long-dead linguistic community, and moreover, the texts themselves can also be very fragmentary."

18/01/2005

.png)