Iraqi Christians launch TV to save Syriac

The demographic collapse linked to wars and confessional violence threatens to make even the idiom of their roots disappear. Initiatives to preserve it include a new TV channel. About 40 students take a course in ancient Syrian at Erbil University, others in the capital Baghdad. Teacher in Nineveh: "It is our history, it is our mother tongue."

Baghdad (AsiaNews) - The demographic collapse of Christians in Iraq (and Syria), fueled by war and sectarian violence, not least the rise of the Islamic State (IS, formerly Isis) that has triggered further hemorrhaging, risks the disappearance of Syriac, an ancient dialect derived from Aramaic.

In use for some three millennia and, in recent years, practiced mainly in homes and families-in some areas even in schools and churches, during religious services-the ancient idiom now risks disappearing as it has for more than half the population in the area. Initiatives to enhance and promote its use include the launch of a new television channel dedicated precisely to the "dying language."

Mariam Albert, a television reporter for the Syriac-language channel Al-Syriania, confirms, "It is true that we speak Syriac at home, but unfortunately I feel that our language is disappearing, as slowly as it is inexorably."

The Baghdad government launched the channel in April to help keep the language alive. With its 40 employees, the network offers a variety of programs ranging from film to art and history. "It is important," the 35-year-old continues, "to have a TV station that represents us.

Many programs are presented using a dialectal form of Syriac, but for news programs the classical form is preferred, but this has the disadvantage of not being understood by everyone.

The stated goal of Al-Syriania, continues TV channel director Jack Anwia, is to "preserve the Syriac language" through what is called "entertainment," without forgetting information and the most significant events for the community. "At one time," the manager continues, "Syriac was a widespread idiom throughout the Middle East," and everyone, including the government, "has a duty to prevent its extinction. "The beauty of Iraq," he concludes, "also consists in its great cultural and religious diversity.

Iraq was once known as the cradle of civilization, the land of the ancient Sumerians and Babylonians who produced the world's first written legal code. Within it is also the city of Ur, according to the Bible the birthplace of Abraham, the father of the three great monotheistic religions. Today it is largely Muslim (Shiite), but is home to Sunni, Kurdish, Christian, and Yazidi communities within it. The official languages are Arabic and Kurdish; before the U.S. invasion in 2003 there were about 1.5 million Christians, later falling below 400,000 as jihadist groups, including Isis, advanced.

Cultural, linguistic and archaeological heritage in Iraq is also a concern for the local Church: since the time when the current Baghdad Patriarch of the Chaldeans, Card. Louis Raphael Sako, had stressed the importance of a policy of rediscovery, preservation and enhancement.

The cardinal termed it a "universal" asset to be preserved just like archaeology, which alone is worth "more than oil." A task incumbent on all citizens and one he recalled in 2016 at the "International Conference to Safeguard Cultural Heritage in Conflict Areas" in Dubai, Emirates, which brought together heads of state and government, scholars, Islamo-Christian religious leaders, activists and experts in history, archaeology and culture.

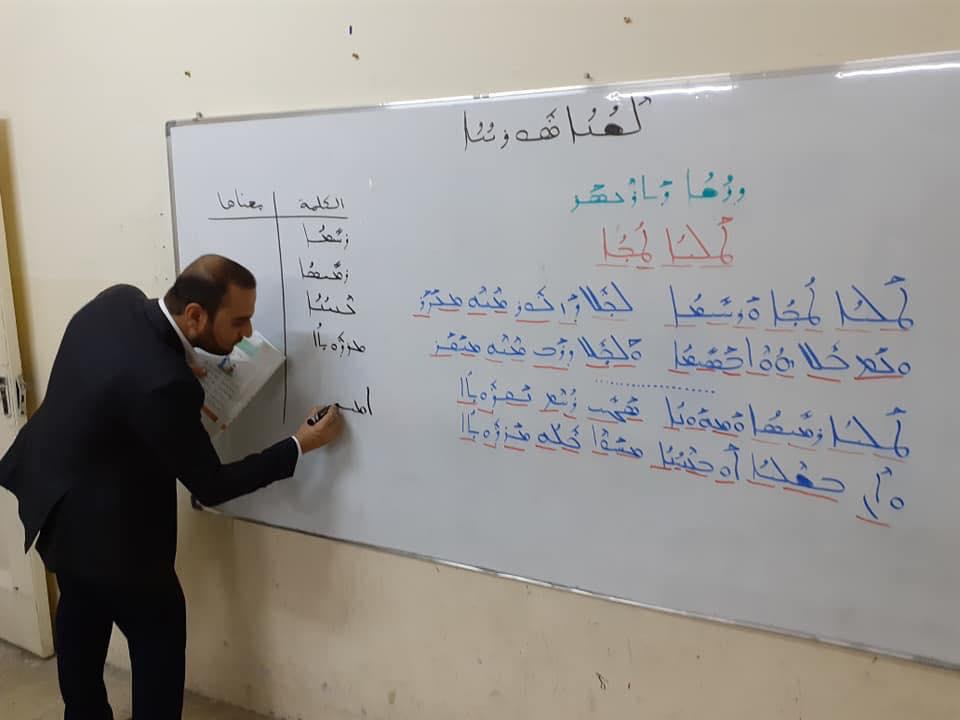

Over the years, the Syriac language has been increasingly "marginalized," as Kawthar Askar, head of the Syriac language department at Salahaddin University in Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan, confirms. "We cannot say it is," he adds, "a dead language ... [but] it is under threat" of disappearing because of migration. The department takes in about 40 students; others take the course at Baghdad University. In total it is taught in about 265 schools scattered around the country, according to numbers provided by Imad Salem Jajjo, head of Syriac education at the Ministry of Education.

Over the years, the Syriac language has been increasingly "marginalized" as Kawthar Askar, head of the Syriac language department at Salahaddin University in Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan, confirms. "We cannot say it is," he adds, "a dead language ... [but] it is under threat" of disappearing because of migration. The department takes in about 40 students; others take the course at Baghdad University. In total it is taught in about 265 schools scattered around the country, according to numbers provided by Imad Salem Jajjo, head of Syriac education at the Ministry of Education.

The last blow to the heritage came with the Islamic caliphate, in 2014, and it was only thanks to the goodwill of some people, including Muslims, that some of the antiquities were saved. These include the current Archbishop of Mosul, Msgr. Najib Mikhael Moussa, who took numerous manuscripts with him before leaving the city.

Today at least 1,700 of these and another 1,400 books-some of them from the 11th century-are preserved in the digital center in Erbil, supported by UNESCO and also cared for by the Dominican fathers. Preservation "will preserve the heritage and ensure its sustainability," the prelate explained. Syriac "is our history, it is our mother tongue," adds Salah Bakos, a teacher from Qaraqosh in the Nineveh Plain. "Teaching Syriac," he concludes, "is important, not only for children but for all segments of our society [...] even if parents say it is a dead language that is useless.

.png)