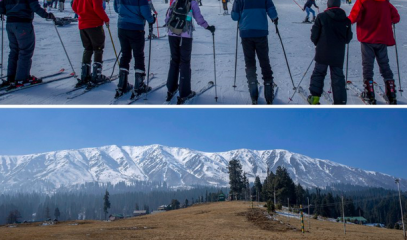

Climate change’s extreme face, a snowless winter in the Himalayas

Temperatures warmer than seasonal averages and low rainfall over the past few months have resulted in what experts describe as the "driest winter" in the region. From Nepal and northern Pakistan to Tibet and Bhutan, a combination of different weather factors is to blame, including the climate crisis and El Niño.

Kathmandu (AsiaNews/Agencies) – In Nepal and other Himalayan countries, it is mid-winter, but not a single drop of rain or snowflake has fallen for four months.

Terrace fields in the mountains are dry, and in the plains winter wheat is drying up. Many mountains are naked and snowless.

“Mukut Himal and many mountains are just bare rock when they should be white with new snow this time of year,” said Madan Sigdel of Tribhuvan University.

Nepal receives an average of 60 mm of rain during the three coldest months. However, the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology has recorded just 1.9 mm of rain so far this winter.

The 2023-24 winter is turning out to be driest in years. There are many causes, starting with global warming, which had the hottest year ever in 2023 along with 2022.

Then there's the El Niño, whose influence causes the waters of the Pacific Ocean to warm, and a drop in westerly winds that bring in cold air and moisture from central Europe, this according to India's Meteorological Department.

Bibhuti Pokharel of Nepal's Department of Hydrology and Meteorology says it is too early to declare the weather models wrong.

“Ours was a long-term forecast, it may not have rained yet, but it might rain more than the average during the remaining one-and-a-half months of winter,” he said.

In fact, extreme weather events induced by the climate crisis may not result in a change in total seasonal precipitation, but rain or snow could fall at once with destructive force.

Last year's winter was also dry with just 12.9 mm of rain, the lowest rainfall recorded in the previous 15 years.

What is more, data show that 12 of the last 18 winters have had below-average rainfall, and eight out of 12 have had droughts.

The trend is for winter rainfall to come at the end of the season, all at once, causing landslides and rivers of mud, this according to the 2023 Synthesis Report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

For Asia, this will mean extreme rainfall variability and drought in both the short and long term. Nepal can expect instead two main consequences.

One is a drop in the country’s total hydropower generation capacity, which declined by 20 per cent in 2023, resulting in higher imports from India to cover the shortfall.

“Power generation has declined drastically, and is expected to go down further as chances of rainfall look slim,” said Prakash Chandra Dulal of the Independent Power Producers' Association, Nepal (IPPAN).

The other consequence is the decline in winter tourism. In 2023, the Himalayan country saw an increase in the number of tourists by over 86 per cent according to data from the Nepal Tourism Board, but this was followed by a 50 per cent drop by the start of 2024.

In neighbouring Kashmir, the situation is worse. Local officials estimate that the number of tourists declined by at least 60 per cent compared to the same period last year.

03/12/2007

12/10/2007

20/06/2023 17:17

.png)